Originally published: December 18th, 2018

The pain of an Aconcagua failure. Oh how it burns!

I’m writing this in Mendoza whilst I look out of the aeroplane window, as it rolls over the tarmac and gets ready to take off to Buenos Aries, for the first leg of my red-eyed four-flight journey to Azerbaijan.

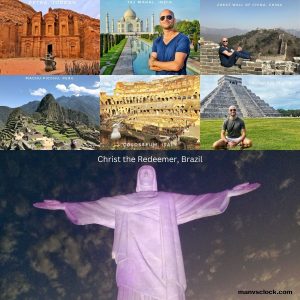

This was supposed to be the victory post, where I talk about how I triumphed over unexpected hurdles and toppled Aconcagua against the odds – the highest mountain in the continent of South America.

Number two for me on the list for the Seven Summits of The World would have been scalped and I would be moving on to the next.

But sadly this is not one of those posts. This is a reflection on failure and disappointment and hopefully, it will help future Aconcagua climbers make an informed decision about when to give it a crack and to leave Argentina with success.

Before I move onto the nitty gritty I want to touch upon something – the word “failure.” It’s a scary and intimidating word and I believe it’s a misunderstood word.

Once I confirmed that the Aconcagua attempt was officially over on social media, many commented on my blogs’ channels with kind words and good intentions.

Amidst the commiserations was a common theme, something along the lines of “it’s not failure because it was out of your control.”

As much as I appreciated the good nature behind the sentiment, the very definition of the word failure is quite simple; “a lack of success.” It doesn’t take into account any fault or control in the absence of the achievement of a personal goal.

It still hurts (as do my frost-bitten lips and nose) and the disappointment is still there, not to mention the case of spending £5,000 and still not completing the task.

The fear of failure is so powerful and profound, that it’s often responsible for us self-imprisoning ourselves into a constant state of mediocracy. We are terrified to even get out of the starting blocks in case we don’t achieve what we set out to do because anyone who has experienced failure knows only too well how heartbreaking it feels.

The pity party is almost over anyway and some moments around that event gave me a fresh perspective, for the better. So let’s talk about what happened and have a chat about the best time to climb Aconcagua.

The journey started on November 30th, with Johnny Ward (onestep4ward.com) who I’m grateful for prompting me with regard to this goal. I’d thought about it before, but “someday” never comes and this needed some serious planning.

Day 1: Gear Check

We met the rest of our crew the night before – a CrossFit fanatic woman from the UK who is joining the Royal Navy next year, an Aussie guy who is set to swim the English Channel and a female Russian mountaineer who was so strong that she was set to climb Ojos Del Salado, the World’s highest volcano in Chile – straight after Aconcagua! Amazing.

Leading our charge up “the mountain of death” was our Russian guide Micha and also a porter who would act as a second guide, Anton.

Russians tend to be very stoic and headstrong, which are perfect attributes to climb a massive, cold, miserable mountain. All of us novices were a little short on gear, but we were able to rent the missing equipment from Elbrus Tours.

Day 2: Plaza Intentes (2800 Metres)

We had an awful, awful, sleazy agent called David Vela who constantly kept turning up late and trying to squeeze extra money out of us and cut costs last minute.

I promise I’m not saying this out of any misplaced bitterness and I’m the antithesis of being tight with my money. I give free travel advice on this blog and I feel like one of the best pearls of wisdom I can give you on this subject is do not use David Vela. Do not consider David Vela. Do not call David Vela. And please, under no circumstances – never, never, ever – go full David Vela.

However, we were driven to 2800 metres to start our acclimatisation and the staff at Plaza Intentes were lovely. We had our last shower for a few weeks and even got to sleep in bunk beds.

Day 3: Camp Confluencia (3400 Metres)

The next day we went up to Camp Confluencia where we would pitch our tents and acclimatise some more. A duo of beautiful mountain angels cooked dinner and also breakfast for us the next day. The backdrop of the start of Aconcagua was deceptively gorgeous, as was this stage of the mountain at Mount Elbrus, Russia.

The drop in temperature and increasing winds were the canaries in the coal mine for what was going to be in store for us as we continued up the mountain.

Day 4: Plaza de Mulas (4300 Metres)

The 8-10 hour hike up to Plaza de Mulas is breathtaking and wouldn’t look amiss on a postcard from rural Mongolia. You’ll need to evolve from trainers/running shoes to hiking boots at this stage as the terrain gets bumpy and cumbersome around here.

Plaza de Mulas was the place that would become the most familiar for us during our frustrating time on Aconcagua. The plan was simple: Set up camp, rest for the night and get cracking up to Camp Canada, which was 5000 metres. (The summit of Aconcagua is just shy of 7000).

Day 5: Camp Canada (5000 Metres)

We woke up to so much snow. Shit! Local guides told us that this was very rare for this time of year.

However, we went for it.

Game on! Moon boots squeezed on and we slowly ascended up to Camp Canada.

Once we got going, the weather wasn’t so bad at all. I’m no expert, it was still bloody cold, windy and uncomfortable but not enough to make me worry that something was seriously up.

After a one-hour rest, we returned back down to Plaza de Mulas, it took us about 8 hours in total and then we visited the on-site doctor for medical checks.

Day 6: Rest Day Back at Plaza de Mulas

This came at a perfect time as three of the seven of us had signs of altitude sickness, so under the doctor’s orders we had to rest. It also gave us an extra day to relax and put forward a potential plan of attack for summiting.

However, Plaza de Mulas was when things really started going tits up. Our dining tent was the worst of the lot and the staff members were doing their very own attempt of “Fawlty Towers, Aconcagua,” (again, don’t use the weasel agent called David Vela).

We put it down as a very annoying occupational hazard and focused on tactics; what’s the weather going to be like in the next few days? Which day do we have as an open window to try and summit?

Every answer seemed negative and this was coming from the experts, not us mere mortals.

Chinese whispers began about people much more experienced than us struggling to get past Camp Canada (only one way) in 10 hours due to horrendous weather conditions. Many needed crampons and usually, you’re not supposed to need them on Aconcagua until the very end, summit day.

The initial plan was as follows; have another rest day, then go back up to Camp Canada but sleep there this time. Then up to 5500, sleep. Then 6000 and summit attempt during the night. This was all created by myself and Johnny scribbling on the back of a teabag box, fuelled by overconfidence and blinded by naivety.

As always, we hopped onto 4G on my phone and relied on the best website and page for attempting to summit Aconcagua: Mountain-Forecast.com

The final cut-off date was the 13th, due to our agreed date with Elbrus Tours.

Day 7-9 Attempt to Nido de Cóndores (5500 Metres)

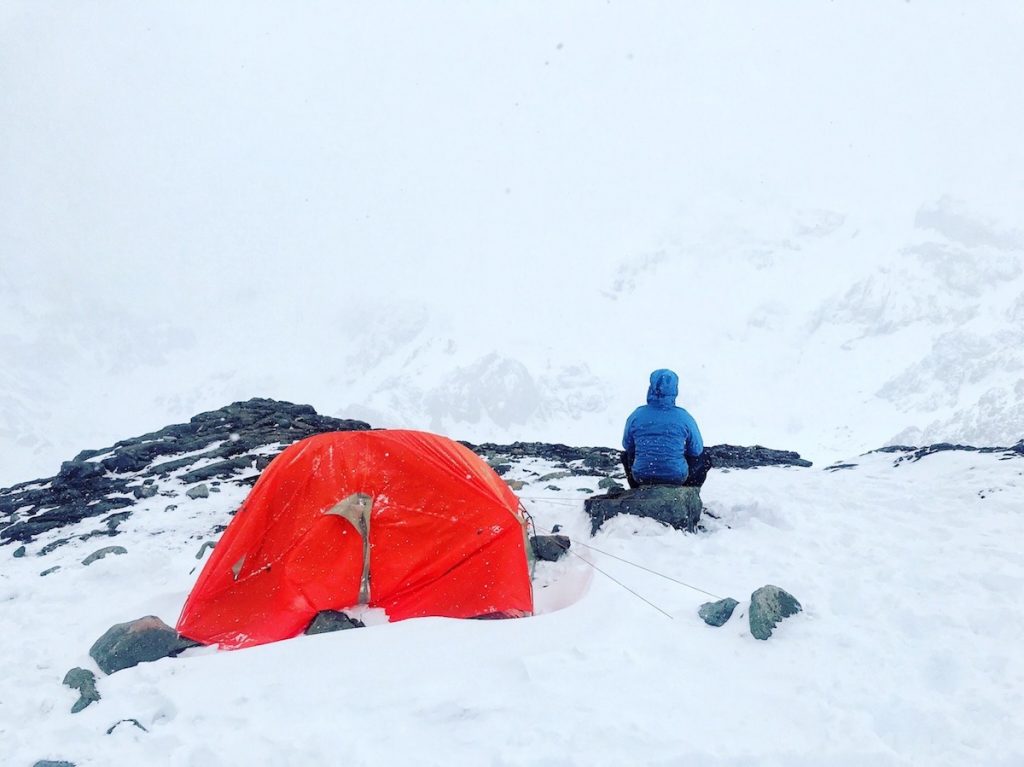

Armed with our hardcore Russian guide, with enough hardcore mountain stories to warrant a book signing and giant queue at Waterstones, it soon became apparent that it wasn’t just the mountain that we were up against, but a factor out of our control; the weather.

To be more precise – it was the wind speed that was the main problem. We didn’t make it to Nido de Condores, as at Camp Canada in the end as we were caught in a fierce snowstorm.

An experienced Argentinian guide of 14 years told us that he was almost certain that nobody would summit in the next two weeks.

It’s the hope that kills and even though we admitted that it was over, we were seduced into shivering over my phone on roaming data to check the weather forecast once again…

Again, the winds were in the red (danger zone) and high 100s. Our Russian guide, Micha kept gently reminding us of how naive we were when we got too big for our North Face boots during our potential summit euphoria.

For a point of reference – our Russian guide, who was as tough as a titanium-encrusted Khabib Nurmagomedov, said that 40 kilometres per hour wind speed was way too dangerous as this could literally blow us all over the mountain, the forecast was up to 100 and even 130 on some days!

As we descended down in the knee-high snow, we broke the hearts of fellow summit dreamers walking up with the bad news, and soon people were evacuating all over the mountain to base camp like an army of ants.

Our 20-day permit cost $580 USD and so we waited out the inevitable – it just wasn’t meant to be. Even though we attempted Aconcagua during shoulder season (the period between the peak and off-peak) the high winds and deep snow that we experienced were very much still out of the ordinary and absolutely nobody summited at all during the whole month.

Aconcagua Failure: Lesson Learned (& What’s Next)

There are a couple of good lessons to learn from this experience and the first one is that I weirdly think failure is good for me in the long run. I haven’t failed at anything for a long time (excluding romantic relationships, ho, ho ho) and we can’t always get what we want in life at the first bite of the cherry.

Defeat asks questions about our personality and inquires about our resolve and bouncebackability is always a good trait to have in our locker. Failure also humbles you and once the pity party is over, you feel almost embarrassed by the melodramatic thoughts that you were initially consumed by.

We thought we saw a corpse on the day that we left, but it turned out that the guy was suffering a pulmonary embolism, which is of course serious, but he survived.

The main event, which brought me right back down to earth arrived a few days later – the sad story of Barney Dobbin, a young fella from Northern Ireland who died after summiting Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador.

The eulogies from two family members of Barney were beautifully profound:

“Although she is distraught, in her sadness Barney’s mother is immensely proud of her son, as he succeeded in reaching the summit.

“It’s a testament to his determination and spirit.”

Barney’s uncle, John Dobbin, offered a moving tribute to the young teacher.

“Barney touched the lives of so many across the globe, and the world has lost a mighty fine son,” he said.

“He explored, discovered, feared not, respected, applauded, loved and cherished all that our mighty planet and inhabitants had to offer.

“On his last day on earth he was as close to the stars as was humanly possible. This was his ultimate and brilliant final achievement.

“He is now the largest star of all, shining brilliantly and beautiful within our hearts.”

Climbing mountains can be a very risky business and it may not make sense to some people why he’d gamble like this, but the harsh truth is that many of us are dead while we are still alive.

I have nothing but respect for this lad, however, his tragic demise obviously made me get a grip and think about how much worse it could have been in Argentina.

Personally, I’m going to announce a new challenge next week which will be by far the hardest physical test that I’ve ever put my body through to date. So I had to get back train hard and put in some serious running miles on my legs for that one, as I need to be fully primed.

Aconcagua – see you again in January 2020. You massive, cold, fickle, ruthless bastard. 🙂 Edit: I went back to Aconcagua a year later and things did not workout out as well as I’d hoped they would! I did not get my revenge story, my war cry against South America’s tallest mountain remains as I tackle the question; how hard is it to climb Aconcagua?